Our Schools

Brookdale Community College has built an esports arena

By Michael L. Diamond

Asbury Park Press

Video and Photos by Peter Ackerman

Key Points

- The Brookdale Eports Arena is equipped with 24 high-end gaming PCs; three console stations; and a raised platform, where the players sit in front of a giant video screen, that fans can watch too.

- Competitive video gaming can get students more involved with their schools, advocates say.

- Students playing the games gain skills that come with playing any sport: teamwork, communication, data science, analytical thinking and brand building.

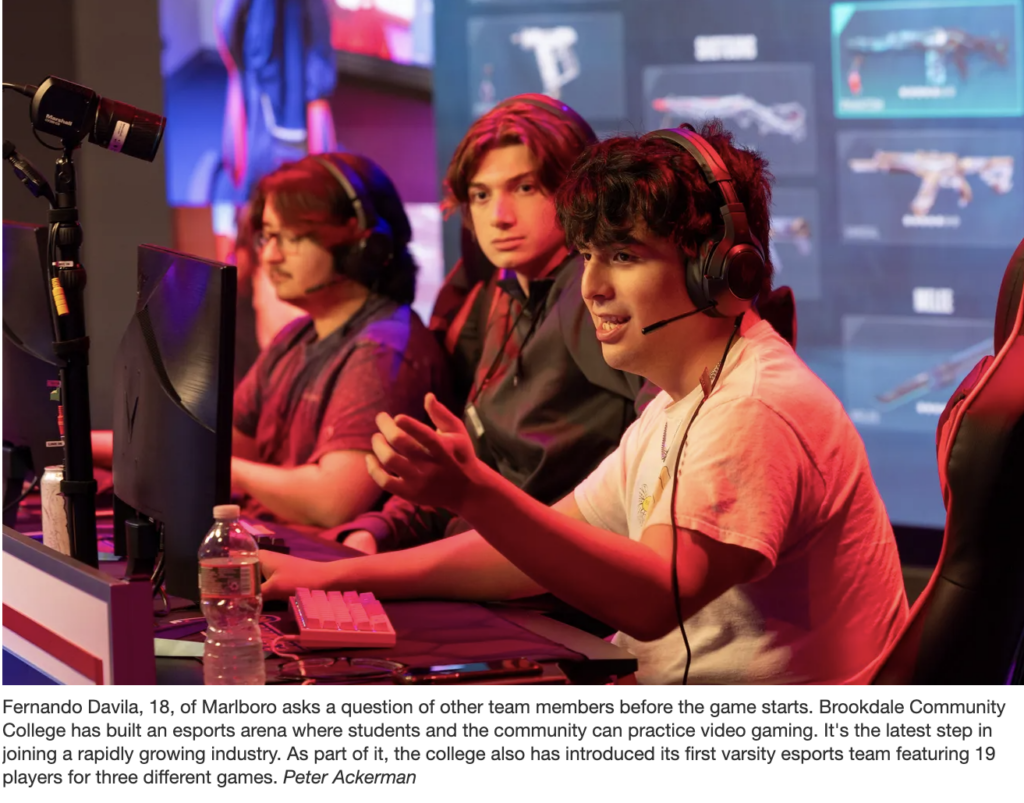

MIDDLETOWN – Will Ahlfeld was visiting Brookdale Community College’s open house last year when he spotted a table with information about the school’s new esports program that soon would include a varsity program for multiplayer competitive video games.

Ahlfeld was intrigued. Growing up, he played video games at his home in Wall for as much as six hours a day, becoming so skilled that he was ranked in the top 500 in North America in one game, Splatoon. The chance to participate on a college team tipped the scales.

“For me, it played a major factor,” Ahlfeld, 18, said of his decision to attend Brookdale.

Brookdale has launched an esports program, featuring three varsity-level teams and two club level teams who gather in the new $1.4 million Brookdale Esports Arena. The players compete against other colleges in the National Junior College Athletic Association, making split-second decisions and protecting each other’s backs in a virtual battle for survival.

With the program, Brookdale becomes the latest New Jersey school to offer gaming as an organized sport, no different from football, basketball or soccer. And educators say the benefits are clear: they are reaching a group of students who haven’t traditionally participated in extracurricular activities and finding social value in a task that can have a reputation for time-wasting isolation.

Some of the stigma can be warranted, experts say. But when the players are in a room together, they are building marketable skills that come with playing any sport: teamwork, communication, data science, analytical thinking, brand building.

“I think this generation still feels connected even though we might judge it (negatively) because it’s on a screen,” said Peter Economou, director of organizational psychology programs at Rutgers University in Piscataway. “I think that belonging, that team aspect, that shared mission really has some positive effects.”

“I think we have to realize, this is the new norm,” he said.

Brookdale’s $1.4 million arena

Ahlfeld started playing Nintendo video games at the age of 10. He said his parents, video game enthusiasts themselves, didn’t mind as long as he got enough sleep. His grades didn’t seem to suffer; he graduated in the top 10 of his class at Wall High School.

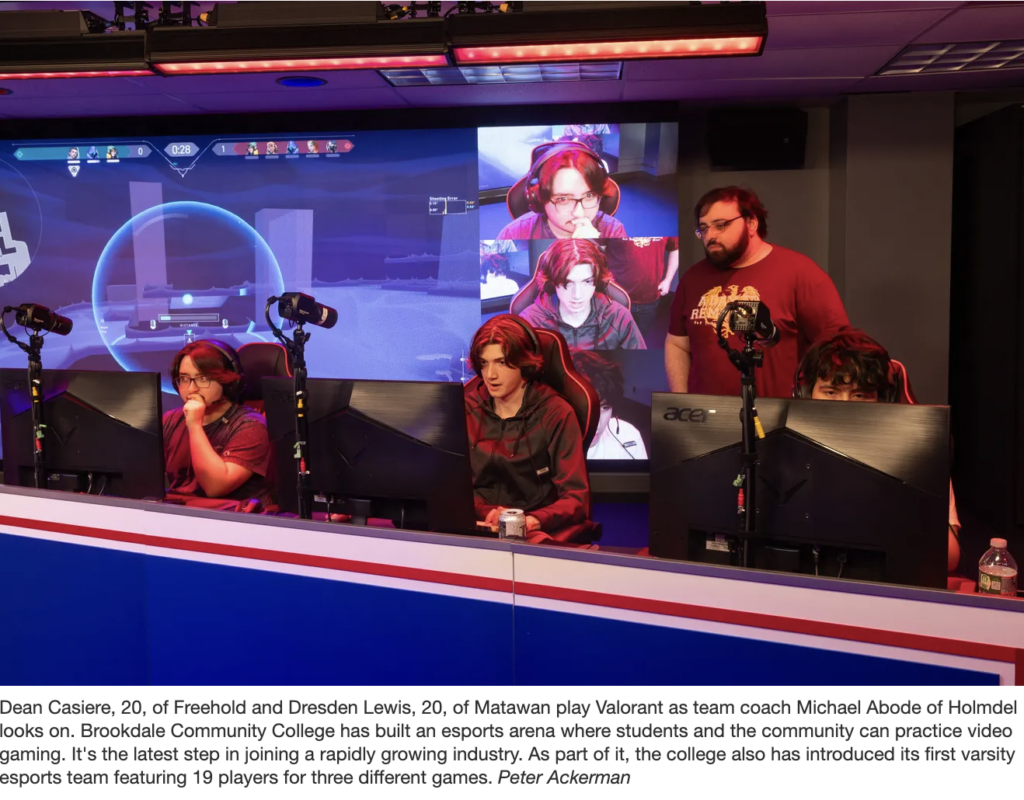

In 2020, Ahlfeld found Valorant, a game played on computers with two teams of five members each. The game features attackers, who try to plant and detonate a bomb, and defenders, who try to defuse the bomb before it goes off. The team that accomplishes their mission gets a point. The first to 13 points wins the match.

Ahlfeld enjoyed the competition and the chance to play with friends in other states. So when he got to Brookdale, he tried out for the Valorant team and made the cut.

These days, Ahlfeld spends his video game time not at home, but at Brookdale’s shining new star, the Esports Arena, a space-agey room on the ground floor of the Student Life Center that’s equipped with 24 high-end gaming PCs; three console stations; and a raised platform, where the players sit in front of a giant video screen, so that fans can follow along and cheer.

The arena also has video production equipment and a booth where students can announce play-by-play for the contests, which can be streamed on Twitch.

The venue is open to other students and the public on weekdays from 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. Students can rent games for $3 an hour, while the public can rent games for $5 an hour.

Keyboards aren’t just for spelling

The program is a bid by Brookdale to tap into a fast-growing industry. Revenue is expected to rise from $227 billion this year to $312 billion in 2027, or 7.9%, thanks to an increase in participants and advertisers that should withstand a slowing global economy, according to PwC’s Global Media & Entertainment Outlook.

Brookdale’s goal: Turn the arena in to a hub for innovation and creativity. And it wants to connect with a group of students who otherwise have few places to go, so that the school — and the local economy — can take advantage of the skills that gamers have developed.

“This is something students are really passionate about,” said Chris Boehmer, the school’s director of esports. “It’s just another outlet that you can compete in and really express yourself.”

Brookdale had tryouts for varsity teams playing Valorant, Rocket League and Super Smash Bros., attracting some 60 students for 19 spots. The school has two club teams as well, for Overwatch 2 and Call of Duty.

The teams’ coaches have experience playing esports in college or, in the case of Valorant coach Michael Abood, the pros. Unlike other sports, the teams usually play the competition remotely, saving the school on bus trips, and ensuring that just about every game is a home game.

The players look like they are in their element. During a Valorant practice last Wednesday night, the team scrimmaged a collection of gamers from some remote place, taking dead aim with their mouses, moving through the dangerous corridors using their W, A, S, and D keys, and giving each other instructions and warnings through their headsets. They looked like they were at NASA’s mission control, trying to land a Mars rover, if the rover was trying to shoot down the other rovers.

They won the practice match handily. The next night, the team beat a tough squad from Dutchess Community College to up their record to 4-0.

Nick Panarella, 18, of Old Bridge, and a member of the Valorant team, said he grew up playing video games. When he got to high school, he managed to keep playing, fitting it in with classes and a job, first pumping gas at Wawa, now helping with day care at an elementary school.

Video games gave Panarella an escape, he said, a rare chance to allow him to focus on one thing at a time. When he enrolled at Brookdale, he stumbled across the esports program on its web site, tried out and made the team.

“It’s always been a dream since I was a kid to play for a team, like, a real team,” Panarella said.

A new sport emerges from the COVID lockdown

There are thousands of students behind Panarella, coming up the ranks. Garden State Esports, the sport’s organizing body in New Jersey, has grown to include 9,000 students from 275 high schools and middle schools.

The group was founded by Chris Aviles, an English teacher at Keyport High School, whose idea for a league took off during COVID, when he and other teachers saw esports as a way to keep their students engaged during a lockdown. Now, he said, the esports elective that he teaches is so popular that he has a two-year waiting list.

What has emerged is its own ecosystem of players and support staff, no different than, say, the high school football team, with one notable exception: Some 42% of esports athletes don’t participate in any other school activities, Aviles said.

“We’re really tapping into a marginalized community of kids and giving them a home-school connection, which we know leads to better learning outcomes,” Aviles said.

Not that there aren’t landmines. The sport has developed a reputation for toxicity, particularly for girls and women who play. And Abood, the former pro, said he had a hard time turning the game off and taking a break.

But they are landmines found in every sport and every workplace. The Brookdale esports program advertises itself as inclusive, laying claim to a rare sports team that is co-ed, Boehmer said.

The teams are off to a strong start this season. The Valorant group in particular is shaping up as a juggernaut, showing resilience when the going gets tough. Their string of victories includes one recent come-from-behind win in which they were down 12-7, facing match point. They rolled off five straight points. Tied at 12 and with the game on the line, they managed to defuse the bomb.

“You can imagine a scenario like that,” Will Ahlfeld said. “The bomb makes an audible ping that it’s defusing. To have that in your ear, it’s that intense. I sweat. I sweat up there sometimes. A big victory comes across all five of our screens. Everybody just starts jumping up and down. I wish someone was recording that.”

Michael L. Diamond is a business reporter who has been writing about the New Jersey economy and health care industry for more than 20 years. He can be reached at mdiamond@gannettnj.com.

Bookstore

Bookstore  Self Service

Self Service  Video Library

Video Library